In Schweitzer’s biographies, not more than two or three lines are devoted to Königsfeld, where he had a house built in 1923 and where he stayed many times during his European visits. In his autobiography, Out of My Life and Thought, he makes only a fleeting reference to it at the beginning of chapter XX, which deals with the two and a half years he spent in Europe, from July 1927 to December 1929. “Between two trips, I stayed with my wife and daughter at the health resort of Königsfeld in the Black Forest, or in Strasbourg”. (Out of My life and my thought)

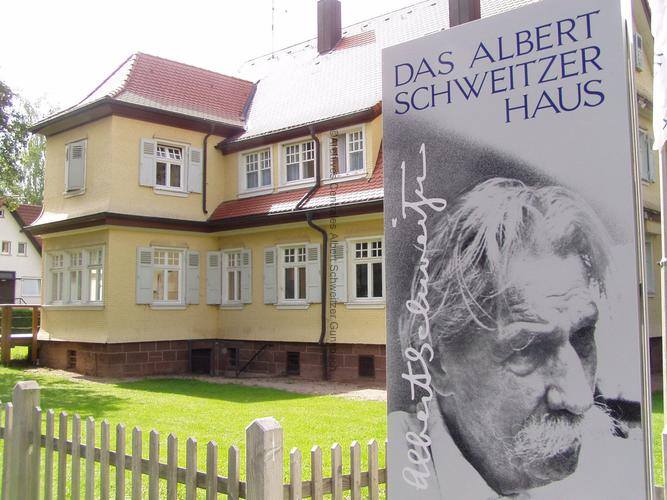

The Königsfeld house

He did not mention that he owned a large house there. He was not yet aware, in 1931 (when he wrote his autobiography), that this house tells an eventful story, that it shows us a facet of his life and his personality, united with a German woman, Hélène Bresslau, and that in the background there is a moment in the history of Germany and… of nearby Alsace. For a long time, it was obscured, pushed to the margins, ignored by biographers who liked to see Schweitzer as “the man from Gunsbach” (and a citizen of the world), but to still recognise him as a Bürger von Königsfeld im Schwarwald, a citizen of Königsfeld, was a little too much, too complicated, blurring the boundaries.

Only in the last ten years or so has attention been drawn to the German side of Albert Schweitzer’s international, transnational life, which lasted well beyond 1918. For us, an example of Europe.

With the prospect of returning to Lambaréné and the need to leave his wife and daughter, Rhena, in Europe, Schweitzer considered moving to Königsfeld around 1922. He hoped that in this health resort, a place of cure and rest, his wife would have a chance to recover from a serious phthisis condition that she had probably contracted in 1917 in the German internment camp at Garaison, in the Pyrenees, on her forced return from Gabon.

Another reason why Schweitzer and his wife chose Königsfeld was that their daughter would benefit from an education inspired by the original methods of the Czech philosopher and educationalist Jan Amos Komensky (known as Comenius) at the Zinzendorf School, run by the Moravian Brothers (Herrnhuter). During her parents’ absences, she was able to stay at the boarding school.

Founded in 1806 by a community of Moravian Brethren from the Herrnhut estate in Saxony, where their ancestors had found refuge during the Thirty Years’ War, Königsfeld retained the religious imprint of a liberal and ‘humanitarian’ pietism. Her friend Hélène Bresslau was a guest at the Waldeck boarding house in May and June 1911, already in need of treatment for her lungs. A year later, in July 1912, it was the destination of their honeymoon (Flitterwochen), at the Waldhotel, “das Ferienhotel zum Liebhaben”.

Ten years later, no longer feeling at home in a French Alsace that was publicly hostile to anything reminiscent of Germany, it was in Königsfeld that they sought new roots, a new Heimat.

The house was quickly built, in less than a year. Schweitzer had helped to draw up the plans and started the work, and knew the architect well, Professor Weigel, who was related to the Mendelssohn-Bartholdy family who lived in Königsfeld. On 1er May 1923, on a fine spring day, the family moved in.

Reproduction of the rural scheme

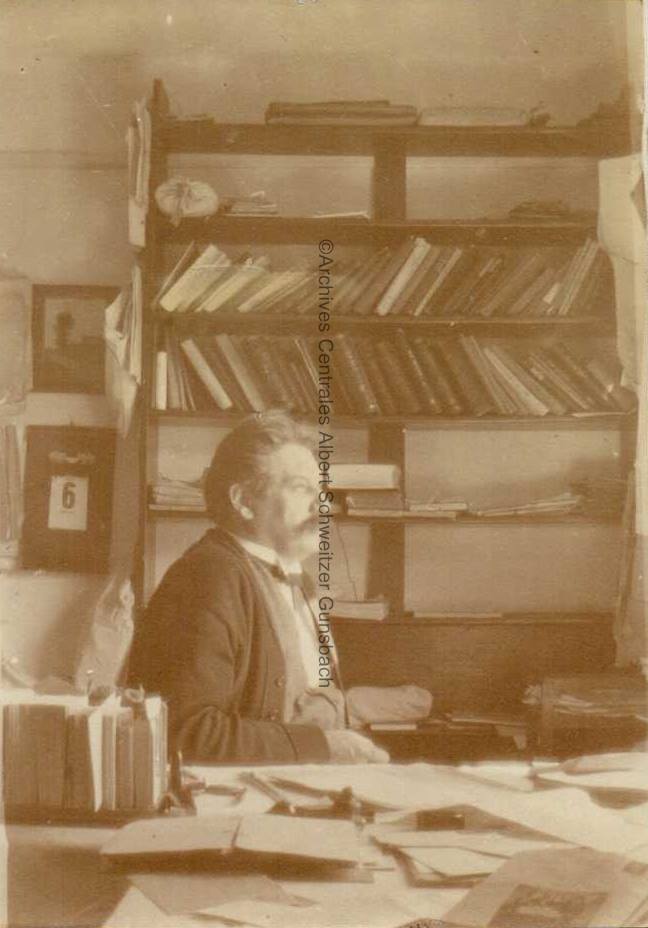

It was agreed that Albert would stay for the whole summer, and he intended to use the notes of his psychoanalyst friend, Pastor Oskar Pfister, to write Memories of his Childhood. On a practical level, his first concern was to cultivate a large vegetable garden (Nutzgarten), and he set to work straight away. He also bought a few chickens for eggs and built them a pen. The dog, Miro, was on watch and good company, just as in Gunsbach there was the faithful and affectionate Sulti.

Basically, Schweitzer was reproducing the pattern of rural life that he had experienced in the village of his childhood – and it was this same pattern of the European countryside that he projected onto the grounds of his hospital in Lambaréné.

14 February 1924, a difficult farewell on a platform at Strasbourg station. Dr Schweitzer took the train to Bordeaux, from where he returned to Gabon to restart the humanitarian mission that had been interrupted by the war. Hélène’s health prevented her from accompanying him this time, not to mention the burden of bringing up Rhéna, who had just turned five.

The winters were to be particularly long and lonely for the 45-year-old mother and her daughter, on the snowy plateau of the Black Forest.

House for rent

When Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich on 30 January 1933, Hélène Schweitzer, née Bresslau, of Jewish descent, no longer felt safe. At the end of the school year, after Easter, she left Königsfeld and moved with her daughter to Lausanne. The house was rented to a professor of theology, who managed to look after it and keep it during the twelve dark years.

Schweitzer returned to Europe three times, in 1934, 1936 and very briefly in 1939, but he never set foot in Germany again. He spent several weeks in Great Britain, giving concerts in London and lectures in Oxford and Edinburgh. From March 1939 to October 1948, almost ten years without a break in the equatorial climate, he was at the helm in Lambaréné.

Hélène lived with her from 1940 until September 1946. She then returned to Europe and found the house in Königsfeld intact. Albert joined her at the end of 1948. When not on tour, he worked through the winter and into March on his new theology manuscript, Reich Gottes und Christentum. On 15 March (1949), he wrote in the margin: “Königsfeld. Ein stürmischer Regentag. Der Frühling naht mit Brausen. (“Rainy day, stormy weather. Spring comes roaring in”). A week later, however, he was in Gunsbach, still writing about the kingdom of God. In the margin, he exclaims: “Endlich wieder daheim in Günsbach” (“Home at last, Gunsbach!”). After all, his first homeland (Heimat) is here in Alsace.

Citoyen d’honneur de Königsfeld

Schweitzer learned in Lambaréné that he had been made an honorary citizen of Königsfeld, and the mayor announced the news in a letter dated 31 December 1949, received at the end of February. In his letter of thanks on 16 February 1950, Schweitzer expressed his joy and gratitude, and recalled the wonderful days he had already spent there with his family. He would return on his next European visits. He played the organ in the Kirchensaal of the Zinzendorf brotherhood on Sundays, and it was there that once, twice, in the autumn of 1951, in his presence, a young girl sang hymns “in her golden voice”. Her name was Ingrid, she was 13 years old, she was in Königsfeld because she suffered from eczema, and she was to become a “sulphurous” star of German cinema and song, Ingrid Caven.

Schweitzer’s last visits to Königsfeld may have been in October 1957. The house was deserted. Weakened by a long stay in Lambaréné, her body exhausted, Hélène had died on 1er June in Zurich. Schweitzer had moved to Gunsbach, “his permanent address in Europe”. No doubt he still had to make return trips to Königsfeld – and it was on one of them, on 25 October 1957, that he stopped off in Freiburg to visit his friend, the Cretan writer Nikos Kazantzaki, who was bedridden in a clinic. “It was a wonderful meeting. He seemed to be recovering, and his recovery was celebrated. Against all expectations, he died the next day.

In 1959, Rhéna inherited the house and, before joining her father in Lambaréné, she sold it for a favourable price (günstig) to the Moravian Brethren community. What were they going to do with it? It took some time. But in 2001, the house was inaugurated as a museum, memory centre and forum. A success story. Cleverly arranged panels tell the essential story, with significant details and documents. Numerous photos, glowing in black and white. Some objects, such as the manuscript box transported on a “Leiterwagele”. Videos. Excerpts from a lecture by the theologian and writer Drewermann.

There is no doubt that Königsfeld, alongside Gunsbach and Lambaréné, was one of the focal points of Schweitzer’s ‘cosmopolitan’ life, a life that was complicated and fragmented, but always powerfully ordered.

Jean-Paul Sorg