On 18 June 1912, Albert Schweitzer married Hélène Bresslau in Gunsbach: they were 37 and 33 years old respectively, which is no longer the age for passionate love affairs but for sensible marriages. So everything went off without a hitch. But who was Hélène really?

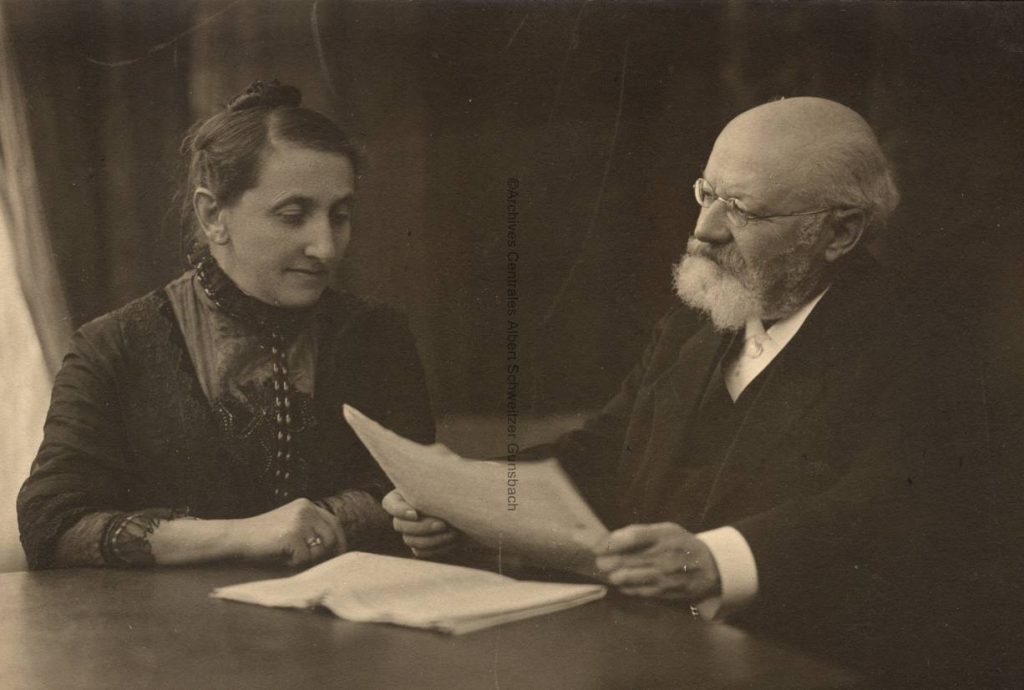

The Bresslau parents

She was born in Berlin on 25 January 1879, the daughter of Caroline Isay and Harry Bresslau, a renowned medieval historian of Jewish origin. After the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, the Germans, wishing to establish the prestige of Germanic culture in Strasbourg, appointed a number of renowned professors to her university, several of whom were Jewish, including, in addition to Bresslau, the physicist Epstein, a great friend of Einstein.

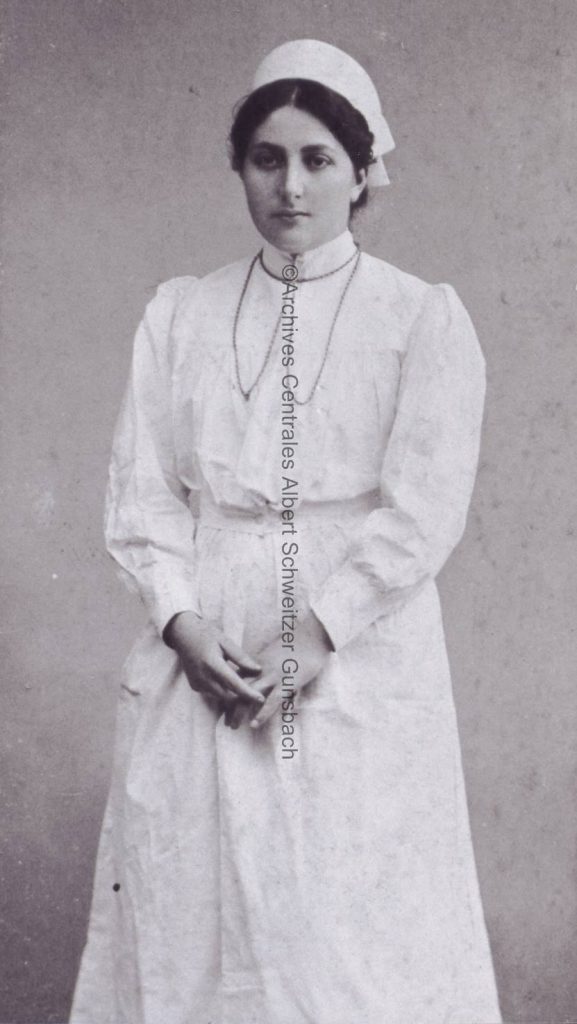

Hélène, care assistant

When they arrived in Strasbourg in 1890, Mr and Mrs Bresslau entrusted Hélène’s spiritual education, and that of her brothers, to the Protestant church, while she attended secondary school until she passed her school-leaving certificate, which opened the door to a career as a teacher. Hélène taught only sporadically, first in England and then in Russia. In 1904, she studied to become a nurse’s aide in Stettin.

As soon as she returned to Strasbourg, she took an interest in social issues and quickly became the city’s inspector for orphans: from 1905 to 1909, she supervised the education of children in families with tact and discernment. Her superiors praised her, including Mr Schwander, who was both mayor of the city and governor of the province, who described her as “a distinguished lady of superior intelligence”.

In 1907, together with a German friend, the daughter of the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, she decided to set up a maternity hospital for young mothers and raised the 15,000 Mark needed to do so. This activity was all the more astonishing given that, at the time, “young girls from good families” hardly ever left their homes, and never unaccompanied.

Meeting Albert

But in August 1898, Hélène had met Albert Schweitzer at the wedding of a mutual friend, Lina Haas. They met again later, Schweitzer having become a lecturer at the University from 1900 onwards, vicar at St-Nicolas, director of studies at the Protestant Seminary, concert organist, co-founder of the Paris Bach Society and writer. Hélène was fascinated by the idea that life does not belong to us alone and that we owe part of it to those less fortunate. So she got close to him and started helping him, along with a few other young people, by relieving him of tedious chores such as copying texts – machines didn’t exist yet – listing proper nouns to classify them in an alphabetical index, composing bibliographies, correcting proofs, and so on. Hélène excelled at this last chore, so precise and meticulous was her mind. Sometimes she would suggest replacing a form of address deemed too familiar with a more classical one, because she was so keen on propriety and distinction.

Their relations were so frequent that Schweitzer confided in her confidentially his plan to give up everything he loved to go and relieve the suffering of those who had no one to help them, as he had done with his most faithful friend, before making the official announcement on 15 October 1905 in the fifteen letters posted in Paris. She took up his cause and defended him against all the critics, which for Schweitzer was a precious comfort. She soon felt that she too had a vocation to help him in faraway Africa, as he could not go alone without an anaesthetist, an operating assistant and a nurse.

So she went to Germany to train in Frankfurt in 1909, where she qualified as a nurse after two years’ study. On her return from Germany in 1912, she got married and prepared to leave. Schweitzer told his childhood friend Anna Schaeffer: “I am not going to the Congo alone; my faithful friend and colleague Hélène Bresslau will accompany me as my wife and medical assistant.”

“Madame Docteur”

As soon as she arrived in Lambaréné, Madame Schweitzer was christened Madame Docteur, because she was so closely associated with her husband’s work. At the same time, she was the indispensable housekeeper, which was no easy task.

Her work was immense, because she had to think of everything, be the Doctor’s assistant and look after the patients. She had to prepare the operations, sterilise the instruments and, little by little, teach others to do the same, starting with Joseph, their faithful assistant. She was an anaesthetist and had to monitor the patient’s breathing, pulse and heart throughout the operation and, at the same time, as the surgeon’s assistant, she had to remember to pass him all the swabs and instruments at the right moment, without him even asking for them, which required constant attention and exemplary skill.

After the operation, she had to monitor the patient until he was fully resuscitated and care for him. She had to dress the patients, and as the number of patients increased, she had to train nurses capable of helping her. Finally, as there were only a limited number of dressing items, who else but Mrs Schweitzer would have cleaned them, boiled them and put them away?

In addition to bandaging, medicines had to be administered and prevented from being misused: ointments were not to be sucked, pills were not to be thrown into the communal pot for the benefit of the whole family, or, despite their magical powers, were not to be sold in exchange for alcohol. The administration of medicines has always required strict control, and two Gabonese nurses were later specially trained to carry out this task.

It was also Hélène’s job to ensure the cleanliness of the inside of the patients’ huts and the orderliness of the outside, to prevent the patients and their families from soiling the hospital environment and coming into conflict with the missionaries.

Hélène’s contribution was considerable, both as housekeeper and as nurse, and at various times she felt exhausted, worn out by the work, exhausted by the trying climate of the continuous steam bath and nervously shaken by the repercussions of the war.

It was all these causes that shattered Hélène’s life and prevented her, after the First World War, from resuming her collaboration with the work that had enthralled her in her youth and to which she had decided to give her all.

Rhéna and Hélène’s illness

The only child from this union, Rhéna, was born on 14 January 1919, when Hélène’s health, then aged 40, had already been impaired by her stay in Lambaréné from 1913 to October 1917 and by her return to France in poor conditions due to their internment, without any reason being given for her fatigue. It was only later, in 1922, that blood sputum revealed the existence of tuberculosis already pronounced by three caverns in the lung, but no one could pinpoint the decisive date of its origin.

It was a catastrophe for the couple, condemning Hélène to reclusion in the sanas, while her husband returned to Lambaréné in February 1924 with his wife’s resigned consent, for which he has never ceased to be grateful. Before that, thanks to the fees from her books, Albert was able to build her a house in Königsfeld, in the Black Forest, in 1922. Unfortunately, Hélène was too weak to run the house and look after her daughter, who was left in the care of a governess, while Hélène was treated in a sanatorium.

She worked tenaciously to regain her strength, and in 1928 she managed to accompany her husband to Frankfurt for the award of the Gœthe Prize, which enabled Schweitzer to build his house in Gunsbach. Sadly, she was never able to move there to make herself useful, and had to give up her place to Madame Emmy Martin, so precarious was her health: a tragic frustration for her.

In 1929, however, believing that she had subdued her illness by dint of her willpower and care, she decided to return to Lambaréné with her husband and resume work there. Schweitzer, after much hesitation, did not want to oppose her return, but he did arrange for her to be accompanied by a guardian angel, the nurse Marie Secrétan, who was responsible for keeping a constant watch over her. However, as soon as the boat reached the tropics, Hélène began to suffer from the climate and her husband thought of sending her back to Europe from Abidjan. But thanks to her unshakeable energy, she eventually arrived in Lambaréné and was delighted to see her great hope fulfilled. She admired the new hospital built in 1926-27, but a persistent fever of 40°C took its toll on her, and she had to be repatriated to Europe after three months.

After 1930, there were new complications, this time political: being of Jewish origin, Hitler’s rise to power prompted her to seek refuge in time, so she left Koenigsfeld to go and live in Lausanne, but not before having had the opportunity, on 22 March 1932, to listen to the speech given by her husband in Frankfurt on the occasion of the centenary of the death of Goethe.

In 1935, she was delighted to welcome her husband to Switzerland to celebrate his 60th birthday with her and Rhéna. Then, in 1937, as her health improved, she and Rhéna left for the United States, where they gave a series of lectures and screenings to publicise her husband’s work. It was thanks to her that Lambaréné was supplied with medicines during the Second World War.

Schweitzer was due to return to Bordeaux in February 1939, where he was to be reunited with his family. Unfortunately, he realised that war was imminent when he disembarked, so he only took the time to send crates of medicines and left on the same boat.

In September 1941, Hélène managed to obtain an exit visa for Lambaréné, where she arrived after an adventurous journey that took her through Portugal and Angola. She left for Switzerland in September 1946.

In 1949, she accompanied her husband on his triumphant trip to the United States, where he had been called to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Goethe in Aspen (Colorado). From that moment on, Schweitzer enjoyed fame and honours from several countries, including the Nobel Prize, which he received in Oslo in 1954 in the company of Hélène.

Hélène, already old and diminished in Oslo, still wanted to return to see her husband. She made her 8e last visit to Lambaréné from January 1956 to May 1957. But as soon as she arrived in Lambaréné, she experienced such respiratory difficulties – which could not be alleviated due to a lack of oxygen – that after the final separation, she had to be rushed back by plane to Zurich, where she was hospitalised and cared for until her death on 1er June 1957 by her daughter and grandchildren. Her ashes were transported to Lambaréné, where they are buried under the date palm that Schweitzer had chosen as the site for his own tomb.

Apart from a few flashes of intense joy at reunions and momentary contact with the work she had loved so much, her life was one of renunciation. Her forced inactivity was keenly felt, and the sense of her frustration weighed down her life with a heavy sadness that she did not want to talk about: hence the silence that enveloped her until the end. Now that she is no more, we can talk about her long suffering and tragic disappointments, despite her efforts to regain her right to act and to participate in the work to which she had dedicated herself.

Madeleine Horst

(text published in Cahiers Albert Schweitzer, No. 52, June 1983)

If you wrote entire volumes, you wouldn’t be able to say anything more beautiful than what you once expressed in two sentences: “Your friendship is my life” and “I feel that all my happiness comes from you”.

Letter from Hélène to Albert, 22 May 1905