Albert Schweitzer was the first to use the phrase “Reverence for Life” to found an ethic that he wanted to be elementary and universal. “I am life that wants to live, surrounded by life that wants to live” was what he believed should be clearly and immediately imposed on every conscience. Behind this phrase, which makes respect for our own life and that of others two absolutely inseparable things, lies much more than ecological thinking.

A precursor of ecology

In the second chapter of The philosophy of civilisation, “How our economic and spiritual life creates obstacles to civilisation“, Albert Schweitzer offers us a criticism of society that is not very tender, yet realistic and surprisingly topical. This is a major work by the Nobel Peace Prize winner, which is unfortunately little known because it has long been out of print in French bookshops. According to this work, the true civilisation would be one that succeeded in spreading reverence for life.

Albert Schweitzer can rightly be considered one of the precursors of ecology, although there is a difference between Schweitzerian thinking and the current trend towards ecology. An important difference that tells us that we may not be doing things in the right order.

While we are used to hearing that biological diversity must be safeguarded in order to guarantee the survival of the human species, Schweitzer insists that the spiritual life, in the broadest sense, of the individual must first be respected. Only the development of an individual’s spiritual life can give rise to the values needed to respect life, and the motivation to apply them.

The community and all its institutions therefore have a major role to play, because they must guarantee individuals the development of, and respect for, their spiritual life. Without this, respect for all other forms of life – human, animal and plant – is likely to remain an idea that affects only the most sensitive or the most privileged, who are not numerous enough to support an entire civilisation.

Although Albert Schweitzer proposes objectives similar to those of ecologists, the method for achieving them is different. For him, reverence for life goes far beyond respect for biological life, which does not go very far if respect for spiritual life is not considered at the same time. An individual who is able to participate in the development of civilisation is a thoughtful individual, who must be able to conceive an ideal, and independent, i.e. free from the constant worry of fighting for his own life in order to realise this ideal for the benefit of the community. “But these days, freedom and time for reflection are on the wane”, he wrote, as a consequence of the overwork that Schweitzer was already talking about around 1915.

For two or three generations now, many people have been nothing more than production machines rather than people,” he writes. All the talk about the moral and cultural value of work means nothing to them any more. The spirit of modern man is bogged down in the inordinate accumulation of overwhelming occupations, in every social milieu. Children are already indirect victims of this overwork. Their parents, caught up in the inexorable struggle for life, cannot devote themselves normally to them, depriving them of things that are irreplaceable for their development. Later, overwhelmed by his own incessant occupations, he is driven to seek easy external distractions. Spending his meagre leisure time alone with himself, thinking and reading, or in the company of friends discussing interesting subjects, would require an effort that he finds repugnant. His physical need for relaxation is to do nothing, to distract himself, to forget, to think of nothing.

This is how the spirit of superficiality takes hold of society and institutions, which in turn aggravate this state of mind by moving in the same direction, such as the media, which “must increasingly flatter the tastes of their clientele and choose the most spectacular and easily assimilated presentation”.

In addition to overwork and the loss of freedom and reflection, there is the compartmentalisation and specialisation of individuals against respect for their spiritual life. Indeed, when our work no longer consists of anything more than the completion of a detail within a much larger project, and we lose sight of the bigger picture, we are driven to depreciate the value of that work.

Specialisation “reduces people to mere fragments of themselves. The results are certainly magnificent, but the spiritual meaning of work for the worker suffers […]. His thinking, his imagination, his knowledge are no longer kept awake by the problems that are always arising anew. His creative and artistic gifts atrophy. Instead of becoming normally aware of his worth in the face of a work that is entirely the fruit of his reflection and personality, he has to content himself with enjoying a fraction of his capacity for success.”

The demonstration is clear: the inordinate increase in material production drives output, and hence specialisation, which is more ‘efficient’, and overwork, which pushes individuals to do nothing outside of work, in which they are not fulfilled either.

This increase in material production leads to “a decline in our spirituality as individuals“. As if all these conditions, which are hardly conducive to respect for life and humanitarianism, were not enough, there is also the “super-organisation of society” which, by imposing ever more complicated regulations and ever more omnipresent control, nips personal initiative in the bud.

I am life that wants to live

Reverence for life, the “I am life that wants to live”, requires the creation of conditions in which the creativity and originality of individuals can emerge, as well as the conditions for their realisation. However, “after a certain point, organisation comes at the expense of the life of the spirit. Personalities and ideas become subject to institutions, instead of dominating them and breathing life into them. […] The more strongly structured the organisation, the more its paralysing action hinders the creative and spiritual activity of individuals. […] Transforming a forest into a carefully tended park can be useful in many cases. But then the rich vegetation that naturally maintained the species for the future is gone.”

So, on the one hand, we have communities that have ceased to be living organisms and have become nothing more than “perfected machines”, and on the other hand, we have overworked individuals who have become very receptive to the ready-made ideas of these communities, who no longer need to justify themselves to “individual reason“.

If life and its creative power can only be expressed through the individual, then respect for life begins with making that expression possible. The unease provoked by Schweitzer’s conclusion at the time of the First World War is only heightened by its topicality: “In the past, society supported individuals; today it crushes them. The bankruptcy of civilised nations, which is becoming more apparent with each passing decade, is precipitating modern man into ruin. The demoralisation of the individual by the collective is in full swing. A man enslaved, overworked, dehumanised, reduced to a mere fragment of himself, a man who alienates his independence of mind and his moral judgement to the super-organised society, a man who is a victim of the obstacles of all kinds that stand in the way of his culture, such is the man who is currently walking the dark path of a dark age.”

Yet Albert Schweitzer is known as the embodiment of optimism. His whole life is a demonstration that the individual is always capable of breaking this vicious circle. Schweitzer’s work is unquestionably that of a free, complete and profoundly human man. He may not have escaped overwork, but that which is imposed from outside by alienating work has nothing to do with that which a free man who wants to realise an ideal imposes on himself. And Schweitzer must know what he’s talking about when he talks about the difficulty of achieving personal initiative in a super-organised society.

When he was director of the Stift in Strasbourg, he tried in vain to found an orphanage. His application to the evangelical missions in Paris in 1905 was rejected, and it is perhaps not entirely coincidental that he finally left for the middle of the virgin forest, accompanied only by his wife Hélène, without asking for any further help from any community or organisation. He was determined to maintain his independence right to the end.

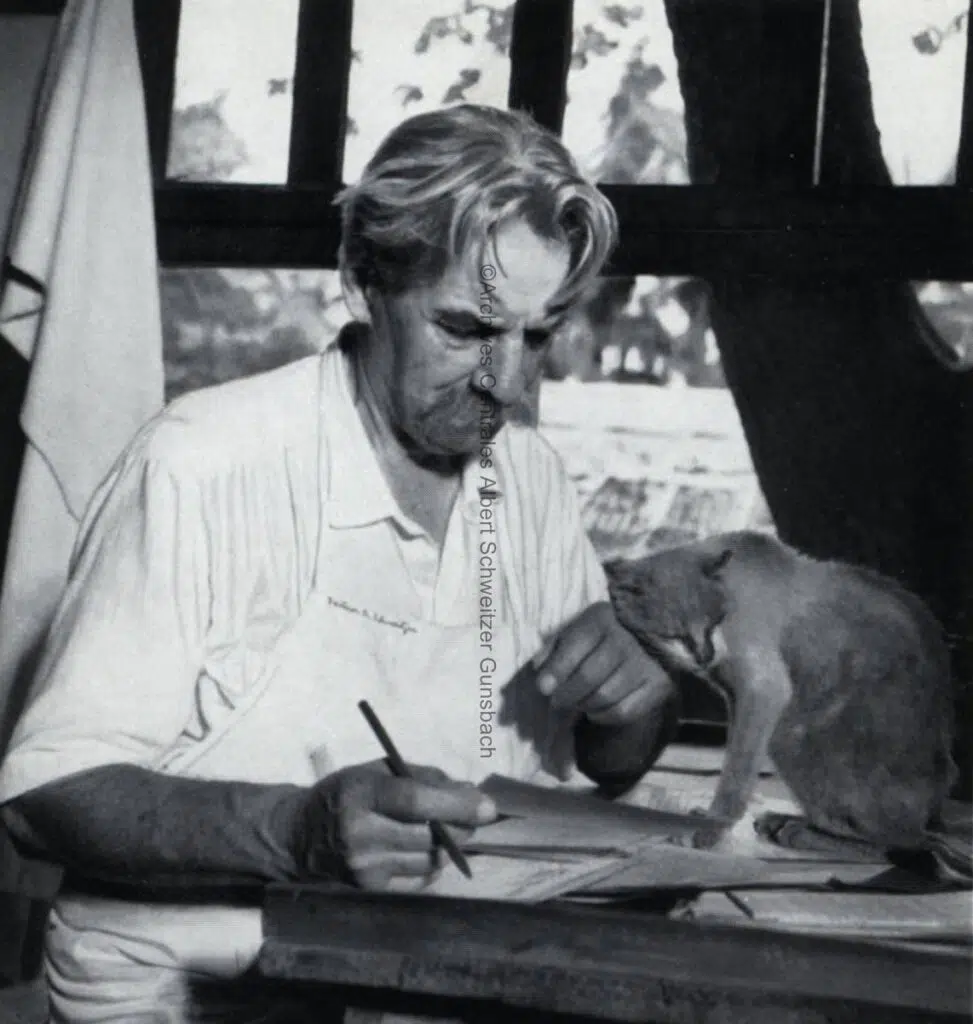

Schweitzer was well aware of the implications of reverence for life, even before he was able to formulate it. His instinct as a free man had already led him to create for himself the conditions conducive to defining this concept that was to become a philosophy. His hospital village is thus a permanent manifestation of reverence for life in all its aspects. Firstly, of course, because thousands of people were treated there: the body’s pains must be relieved so that the spirit can be free, as Schweitzer said. But also because thousands of animals were cared for, and a palm tree was not sacrificed for a simple Christmas party: it had to be dug up and then replanted.

It’s in the feeling of usefulness that we realise ourselves

Patients were free to come and go, to lead their lives without having their customs disrupted, and to work too, because the hospital’s operations required it, of course, but above all because it’s in the feeling of usefulness that we realise ourselves, like those mentally ill people who looked after the garden and asked to stay in the hospital after they had recovered.

Many employees were also able to fulfil their vocation here, and Schweitzer demanded a certain versatility. There was no question of specialising and not being able to replace someone else when circumstances required. In a way, it was a small company corresponding to his ideal that Schweitzer tried to recreate in Lambaréné.

Not crushing an insect unnecessarily and enabling individuals to reach their highest degree of spiritual realisation are two aspects of one and the same ethic. If one is neglected, the other will never be fully achieved. All the wills of life are equal. “I am life that wants to live, surrounded by life that wants to live”.

Jenny LITZELMANN (Published in Les Saisons d’Alsace, special edition February 2013, p.34-41)