Albert Schweitzer in the media

1. Albert Schweitzer

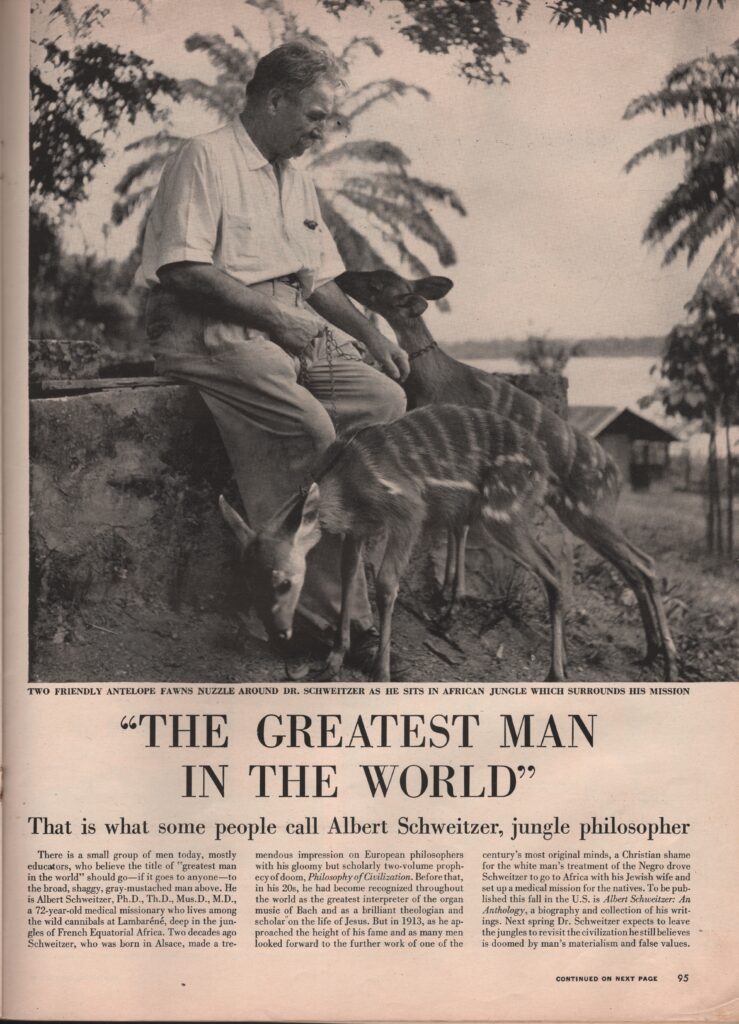

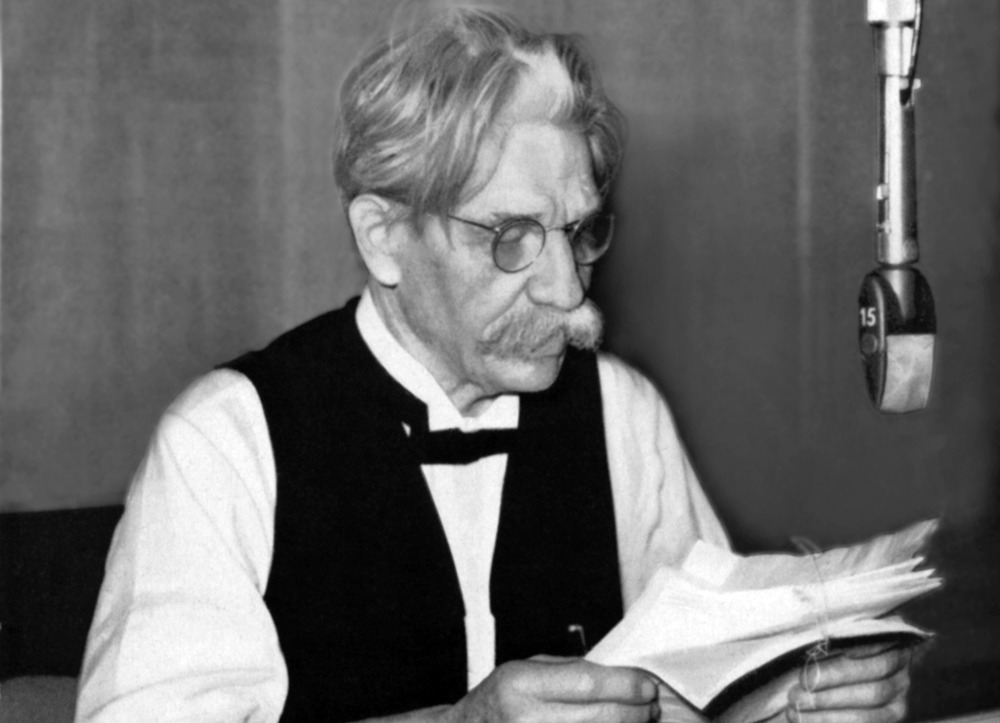

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) was a musician, philosopher, theologian, doctor and pioneer of humanitarian aid. In 1913, he founded a hospital in Gabon, and in 1915 he developed the “Reverence for Life” ethic. In the 20th century, Americans considered him to be “the greatest man in the world”. His correspondence with numerous personalities from all over the world is immense (J.F. Kennedy, Albert Einstein, the Queens of England, Belgium and the Netherlands, Abbé Pierre, the Dalai Lama, etc.). He inspired figures such as Rachel Carson, Karen Blixen, Joséphine Baker and the founders of Doctors Without Borders. When he died, Martin Luther King reacted by writing that it was “one of the brightest stars in the human firmament” that was extinguished with Schweitzer. “Compared to some of the giants who have received this prize – Schweitzer and King; Marshall and Mandela – my achievements pale in comparison”, was how Barack Obama began his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in 2009.

Albert Schweitzer remains one of the best-known French Nobel Prize winners in the world, but is virtually absent from the national media in France…

2. Why ?

It was not a foregone conclusion between France and this Alsatian, who never wanted to deny what he owed to Germany, in his education, his university training (three doctorates in philosophy, theology and medicine), his life… When he arrived in a French colony as a German in 1913, he was suspected of being a spy for Germany. In 1917, he and his wife Hélène Bresslau were arrested in their hospital and interned as civilians in the south of France. In 1919, the French government ordered pastors to say in their sermons that the French victory had been willed by God. Schweitzer disobeyed, telling his parishioners that there had been no victory, that it was a failure of humanity and that we had all failed, together, in the commandment not to kill. Shortly afterwards, he was put under surveillance by the French police, who suspected that his concerts throughout Europe, which he used to raise funds for the hospital, were in fact a cover for “Germanophile propaganda”…

When the Americans revealed Schweitzer’s work in Gabon, awards poured in from all over the world, including France, which awarded him the Légion d’Honneur in 1948.

When he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, the French media were quick to highlight his French citizenship. He was urged on both sides of the Rhine to declare his true citizenship, which of course he never did. He has been firmly opposed to all forms of nationalism since his youth, and already regretted that those who do not recognise national borders are constantly obliged to justify themselves. He prefers to say that he is “a Gunsbach man and a citizen of the world”.

In 1957, following in the footsteps of his friend Albert Einstein, who had died in despair, he took up the fight against atomic weapons and nuclear testing. He launched 4 appeals on Radio Oslo, which were broadcast around the world and translated into many languages. He once again became a target for the media and politicians, who tried to undermine his discourse by spreading rumours, criticising his model of hospitality and alleged racist or colonialist behaviour, not hesitating to use facts denied by local people. Gabonese people who worked with Schweitzer are still trying to change this negative image that has taken root in some minds, but limited resources and the fact that Schweitzer’s works (around thirty works) are poorly translated into French make this difficult.

3. “Reverence for life“

Schweitzer’s work is prolific, including his writings on Christianity, Indian and Chinese religions, his work in Gabon, the music of Bach, the philosophies of Kant and Goethe, his profound reflection on the decline of Western civilisation and the ethic he proposed in 1915 to regenerate it: Reverence for Life, which was the guiding principle of his thoughts and actions. He was a pioneer in many fields, and his gigantic and timeless body of work, as well as his unfailing optimism, make him a highly inspiring figure. Our aim is to help the French public (re)discover him.

4. Association Internationale pour l’œuvre du Dr Albert Schweitzer de Lambaréné

Today, the AISL, founded in 1930 by Schweitzer, has the mission of disseminating this ethic and making his work more widely known. It brings together associations in several countries in Europe, America, Africa and Asia.

The AISL has its headquarters in his house in Gunsbach, where he lived between his visits to Africa and from where links between Europe and the hospital in Lambaréné were organised. It was opened to the public in 1967, two years after Schweitzer’s death, and has recently undergone major restoration and extension work, so that it can continue to pass on the ethic of Reverence for Life to new generations, as its illustrious inhabitant wished above all else.

Jenny Litzelmann

“I call humanity to the ethic of reverence for life. This ethic makes no distinction between a more valuable life and a less valuable life, between a superior life and an inferior life. It rejects such a distinction, because accepting these differences in value between living beings basically amounts to judging them according to the greater or lesser similarity of their sensitivity to ours. But this is an entirely subjective criterion. So who among us knows what significance the other living being has for itself and for the Whole?

Albert Schweitzer, Appeal to Humanity, 1964

The consequence of this distinction is then the idea that there are lives without value, whose destruction or deterioration would be permitted. Depending on the circumstances, by worthless life we mean insects or primitive peoples”.

“By its very nature, then, nationalism consists of a pathological interpretation and transformation of the realities of political life, against a backdrop of megalomaniacal and paranoid ideas, the products of a delirious imagination. And by operating in this way, in mindsets, speeches and actions, nationalism only makes reality permanently worse.

Albert Schweitzer, Psychopathology of Nationalism, 1915

A people’s ideas of grandeur become a state of affairs for other peoples to reckon with, reinforcing their own fears of persecution. It then acts in the same way on its neighbours. This is how an initially imaginary threat becomes an actual threat. Sick imagination and perceived reality form a circle in which increasingly insane representations and increasingly insane situations corroborate each other, fatally inclining politics towards absurd actions and coups de force”.